Evidence #532 | February 11, 2026

Book of Moses Evidence: Forbidden Knowledge and Secret Combinations

Post contributed by

Scripture Central

Abstract

Forbidden knowledge and secret combinations within the Book of Moses and Book of Mormon align very well with several extrabiblical traditions.Secret Combinations in the Book of Moses and Book of Mormon

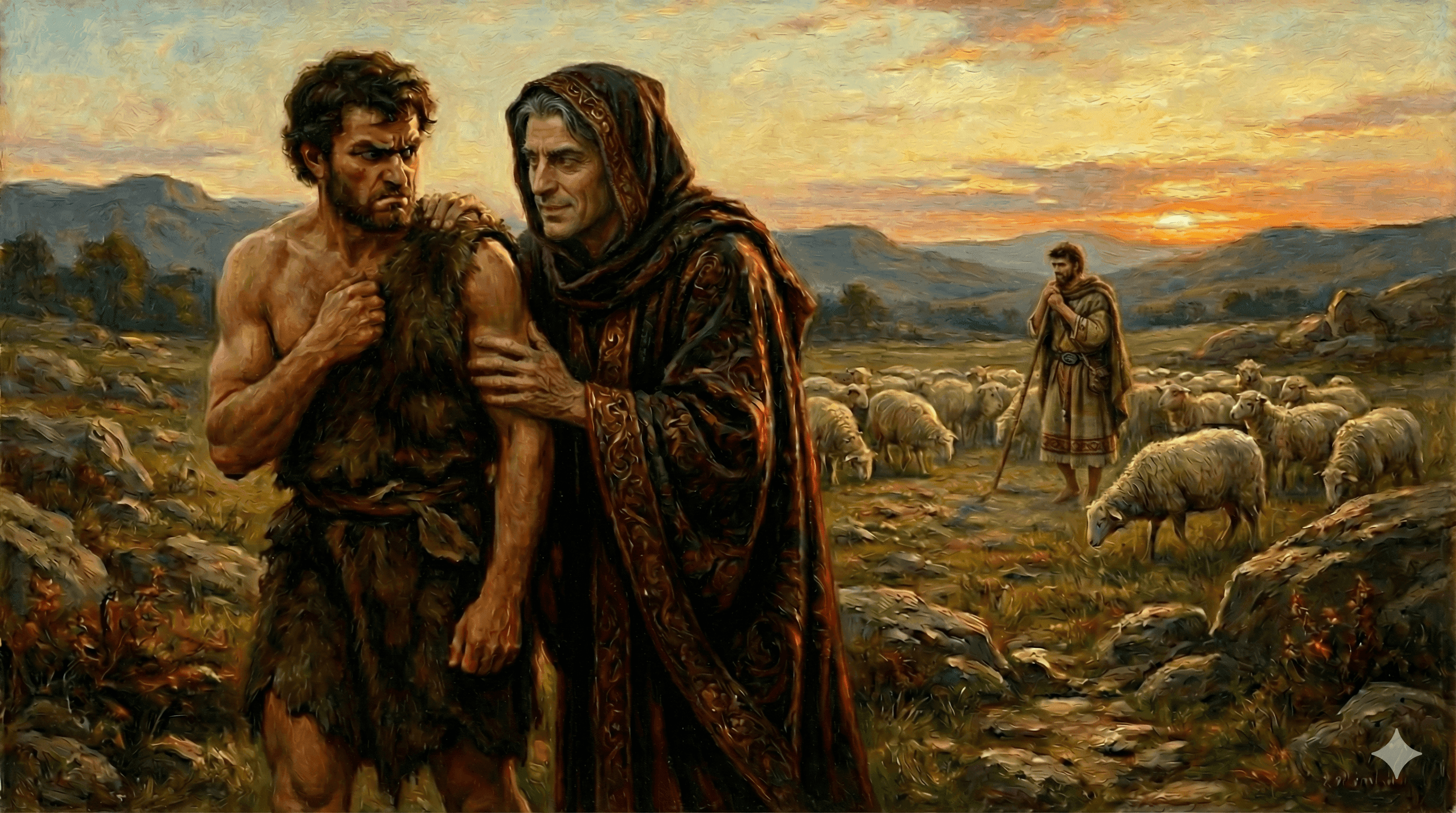

One prominent theme in the Book of Moses is the introduction of dark and sinister secrets among the people. This information, not present in the corresponding account in Genesis 4, begins when Cain entered into a covenant with Satan:

And Satan said unto Cain: Swear unto me by thy throat, and if thou tell it thou shalt die; and swear thy brethren by their heads, and by the living God, that they tell it not; for if they tell it, they shall surely die; and this that thy father may not know it; and this day I will deliver thy brother Abel into thine hands. And Satan sware unto Cain that he would do according to his commands. And all these things were done in secret. And Cain said: Truly I am Mahan, the master of this great secret, that I may murder and get gain. (Moses 5:29–31)

One interesting feature of the Book of Moses is the apparent wordplay on the name of Cain. The text twice emphasizes that his primary goal was to “get gain” (Moses 5:31, 50), a theme that is picked up and expanded considerably in the Book of Mormon’s traditions of antediluvian wickedness. In that text, Cain’s covenant with Satan provides a precedent for secret combinations among the Nephites and Jaredites, as well as a pattern for getting wealth and power through robbery.1 This relates back to Cain’s introduction in Moses 5:16 (cf. Genesis 4:1): “And Adam knew Eve his wife, and she conceived and bare Cain, and said: I have gotten a man from the Lord.” As explained by Matthew Bowen, the Hebrew word for “gotten” (qānîtî) in this passage can also be understood as “I have gained,” or “I have acquired.”2 Thus, the theme of obtaining wealth and power through the use of forbidden knowledge in the Book of Moses seems to thematically play on the Hebrew meaning of Cain’s name.3

Eventually, the text comments on the spread of this secret combination among Cain’s posterity. While some of these themes arise in the Genesis account, the Book of Moses again provides a substantial expansion:

For Lamech having entered into a covenant with Satan, after the manner of Cain, wherein he became Master Mahan, master of that great secret which was administered unto Cain by Satan; and Irad, the son of Enoch, having known their secret, began to reveal it unto the sons of Adam; Wherefore Lamech, being angry, slew him, not like unto Cain, his brother Abel, for the sake of getting gain, but he slew him for the oath’s sake. For, from the days of Cain, there was a secret combination, and their works were in the dark, and they knew every man his brother. Wherefore the Lord cursed Lamech, and his house, and all them that had covenanted with Satan; for they kept not the commandments of God, and it displeased God, and he ministered not unto them, and their works were abominations, and began to spread among all the sons of men. And it was among the sons of men. And among the daughters of men these things were not spoken, because that Lamech had spoken the secret unto his wives, and they rebelled against him, and declared these things abroad, and had not compassion. (Moses 5:49–53)

Overall, the Book of Moses features several details not contained in the account in Genesis. These include (1) Cain’s interactions and covenant with Satan, (2) sinister secrets and abominable oaths revealed to mankind by Satan, and (3) the sharing of these secrets with wives. Remarkably, each of these ideas has notable parallels in ancient and medieval traditions.

Satan’s Interactions with Cain

Although the Genesis account says nothing about Cain interacting with Satan, this idea is developed in a number of extrabiblical sources.4 For instance, an early Jewish account often referred to as the Apocalypse of Moses reports that Eve had a disturbing dream about Cain’s impending murder of Abel. After she reported the dream to Adam, he declared, “Perhaps the enemy is warring against them.”5 This reference to “the enemy” seems to be an obvious allusion to Satan. Just a few short chapters later, when narrating the Garden of Eden episode, Adam explained that “the enemy gave to [Eve] and she ate from the tree …. Then she gave also to me to eat.”6

An ever clearer depiction comes from the Apocalypse of Abraham, which portrays the patriarch Abraham as witnessing a vision of the beginning of human history: “And I saw, as it were, Adam, and Eve who was with him, and with them the crafty adversary and Cain, who had been led by the adversary to break the law, and (I saw) the murdered Abel (and) the perdition brought on him and given through the lawless one.”7 This again tracks well with Satan leading Cain to kill his brother, as described in the Book of Moses. Of particular interest is the Lord’s statement to Cain in Moses 5:24: “For from this time forth thou shalt be the father of his lies; thou shalt be called Perdition; for thou wast also before the world.”

Early Christian writers also picked up on this theme. As summarized by Joseph Witztum, “According to many Christian sources, Syriac and others, Satan instigates the murder.”8 As mentioned by Theophilus of Antioch: “When Satan saw … Abel pleasing God, he worked upon his brother called Cain and made him kill his brother Abel.”9 This idea is echoed in a Syriac dialogue poem: “The cunning Evil One incited him [Cain] and indicated to him that he should shed blood.”10 It turns up again in the writings of Isaac of Antioch:

For the Evil One had encouraged (labbṭēh) him greatly / lest he hesitate to do so. The Evil One and his troops consulted / with Cain, the disciple of falsehood, so that they might prevail over the glorious one, / the one who rebukes their actions. The Evil One said to Cain: / “Kill your brother who persecutes us, / and show us a sign that you love us / in the death of this son of your mother.11

These statements particularly parallel the idea that “Cain loved Satan more than God” in Moses 5:18, as well as in Moses 7:33: “And unto thy brethren have I said, and also given commandment, that they should love one another, and that they should choose me, their Father; but behold, they are without affection, and they hate their own blood.” The Book of Moses thus develops the theme of Cain and his followers as switching their filial allegiance from God to Satan.12 In particular, Cain’s “sign” of his love for Satan, which correlates well with the secret covenant he makes with Satan in the Book of Moses, may be a counterfeit of the true signs and tokens associated with Latter-day Saint temple worship.13

Other accounts provide even more detail. In the Conflict of Adam and Eve, Satan appeared to Cain at night and enticed him to be jealous of his brother Abel, due to Adam and Eve’s intention to marry Abel to Cain’s “beautiful sister,” while Cain would end up with the “ill-favoured sister.” Satan then declared, “Now, therefore, I counsel thee, when they do that, to kill thy brother; then thy sister will be left for thee; and his sister will be cast away.”14 This echoes the notion that Cain “rejected the greater counsel which was had from God” (Moses 5:25). Satan later promised Cain, “Yet if thou wilt take my advice, and hearken to me, I will bring thee on thy wedding day beautiful robes, gold and silver in plenty.”15

The Cave of Treasures likewise reports that “Satan entered Cain so that he would slay his brother for Levudah’s sake [the beautiful sister), and (also) on account of his offering being rejected and not accepted in front of God while Abel’s offering was accepted.”16 Although there are obvious differences between these details and the account in the Book of Moses, they thematically resonate with Satan’s secret agreement with Cain, followed by Cain’s declaration in Moses 5:31: “Truly I am Mahan, the master of this great secret, that I may murder and get gain.”17 Notably, depictions of Cain’s avarice—which is found in Joseph Smith’s revelations and extrabiblical sources—is not presented in the Bible itself.

Other Christian accounts indicate that it was Satan who first revealed to Cain specifically how to kill his brother. According to The Book of the Bee, it was held that “Satan appeared to [Cain] in the form of wild beasts that fight with one another and slay each other.”18 These were apparently intended to show Cain how the evil deed was to be accomplished. In the Armenian story of Abel’s death, “Satan came in the form of two ravens, and the one took a sharp stone, struck the other with it in the throat and killed him, and the stone was sharp as a razor.”19 A related Georgian version of the text states that “two demons resembling Cain and Abel came. Now one demon reproached the other demon. He became angry with him and took a stone sword which was of a transparent stone.” After Cain saw what the evil spirits did, he took up the sharp stone and killed his brother in the same fashion.20 These sources mirror the idea in the Book of Moses that Cain obtained some sort of secret or novel information from Satan, in connection to Abel’s murder.

Secrets Revealed by the Watchers

These Jewish and Christian traditions about Satan—the archetypical fallen angel—echo the well-known myth of the fallen angels as reported in various ancient and medieval sources, in which heavenly beings revealed forbidden knowledge to mortals, typically as a prelude to violence and in conjunction with their lust for the daughters of men.21 The Genesis account may preserve a portion of this myth when it describes advancements in civilization among Cain’s posterity in Genesis 4:21–22:

And Adah bare Jabal: he was the father of such as dwell in tents, and of such as have cattle. And his brother’s name was Jubal: he was the father of all such as handle the harp and organ. And Zillah, she also bare Tubal-cain, an instructer of every artificer in brass and iron: and the sister of Tubal-cain was Naamah.

These details are also provided in Moses 5:45–46, but then the Book of Moses immediately expands the discussion to include the secret knowledge that was handed down to Lamech from Cain (Moses 5:49). In other words, the Book of Moses seems to use the advancements in human technology—including the mention of metallurgy and the crafting of instruments—as a segue to discuss forbidden knowledge revealed by Satan, who in the previous chapter was described as being “cast down” from heaven (Moses 4:3). While nothing about the Genesis account, at least when read in isolation, hints at such an association, various extrabiblical sources do.

Summarizing the tradition of the fallen angels as preserved in 1 Enoch, Annette Reed explains:

The teachings of the fallen angel Asael, for instance, are placed at the origins of the human arts of mining, metal-working, weaponry, shield-craft, cosmetics, dyes, and jewelry (1 Enoch 8:1). Exiled from their heavenly homes, other Watchers are said to show humankind how to wrest knowledge from the skies, by divining auguries from celestial and meteorological phenomena (8:3). Other teachings, associated particularly with the angelic leader Shemiḥazah and with the skills revealed to the Watchers’ wives, evoke an association with “magic”: sorcery, charms, the cutting of roots, and plant lore (7:1; 8:3).22

A similar account is given in 1 Enoch 69:4–26. The mention here of the crafting of weapons is repeated, but most of the other items in the previous list are omitted and several other types of knowledge are mentioned instead, including the secrets of wisdom, the craft of writing, the process of committing abortion, and—most interestingly—a name-associated oath. Concerning this last item, the text reads:

This is the number of Kasbe’el, the chief of the oath, which he showed to the holy ones when he was dwelling on high in glory, and its (or his) name (is) Beqa [perhaps corresponding to “YHWH the Lord” or “YHWH God”]. This one told Michael that he should show him the secret name, so that they might mention [or remember or memorize] it in the oath, so that those who showed the sons of men everything that was in secret might quake at the name and the oath. And this is the power of this oath, for it is powerful and strong, and he placed this oath in the hand of Michael. (1 Enoch 69:14–15)23

This name-associated oath that involves power and strength and which was given into the “hand” of Michael—whom Latter-day Saints view as the pre-mortal Adam—is rather fascinating. In his commentary on these passages, George Nickelsburg notes that this obscure account seems to be a fragment of a longer narrative that isn’t extant and that in the text’s present form it is “unclear exactly what is taking place.”24 While discerning the original details and full intent of the story may be impossible, Nickelsburg gives the following interpretation:

Kasbe’el tricked Michael into revealing the secret of the divine name. Kasbe’el, in turn, revealed the name to his angelic colleagues, who used it in the oath that they swore as they conspired to rebel against God. Verse 14 may also imply that they revealed the divine name to humanity (“those who showed the sons of men everything that was in secret”).25

The text then goes on to describe “the secrets of this oath” which are themselves said to be “sustained by the oath.” The reader is informed that, in connection to the oath, the “heaven was suspended before the creation of the world; and forever!” Moreover, by the oath, “the earth is founded upon the water … the sea was created … the depths are made firm … the sun and the moon complete their courses of travel … the stars complete their courses of travel …. This oath has become dominant over them; they are preserved by it and their paths are preserved by it (so that) their courses of travel do not perish” (1 Enoch 69:16–26).26 In other words, this oath was present before the foundation of the world and is the power by which all things were created and by which they are sustained and preserved. When taken together, this name-associated oath and the manner in which it was given to Michael intersects on multiple levels with Latter-day Saint conceptions of priesthood ordinances, authority, and power.27

All of these details resonate well with the Book of Moses, which implicitly frames Satan’s secret combinations as a corrupted form of true heavenly secrets and priesthood-related ordinances. Satan told Cain, “Swear unto me by thy throat, and if thou tell it thou shalt die; and swear thy brethren by their heads, and by the living God, that they tell it not” (Moses 5:29). Notice that, similar to the account of 1 Enoch, Satan prescribes swearing by God’s name, suggesting that this key word was part of the oath formula in antediluvian times.28 This was also part of a “great secret” that Cain felt Satan had revealed to him (Moses 5:29–31). Later, the reader is told that Lamech likewise slew a man “for the oath’s sake” (Moses 5:50).

Interestingly, among the extant manuscripts of 1 Enoch, there is some divergence about what precisely was revealed to humans by the heavenly Watchers. Not only do different books within 1 Enoch provide different details with varying degrees of specificity, but there are qualitative differences as well. Concerning 1 Enoch 16:3, Annette Reed explains, “Where the extant Greek and Ethiopic versions diverge is on the question of what exactly the Watchers knew—and, hence, on the question what precisely they taught to their wives. The Greek suggests that these angels knew and revealed heavenly secrets, while the Ethiopic asserts that the fallen angels possessed no real heavenly knowledge but only rejected or worthless knowledge.”29

The Book of Moses, however, may be able to somewhat account for this seeming paradox, as it implicitly presents Satan’s sordid oaths and secret combinations as counterfeits of God’s true covenants and ordinances. As we learn in Moses 5:58–59, “the Gospel began to be preached, from the beginning, being declared by holy angels sent forth from the presence of God .… And thus all things were confirmed unto Adam, by an holy ordinance.” Thus, whatever Satan or his demonic followers might have revealed to mankind may be simultaneously a reflection of true heavenly knowledge (inasmuch as such knowledge is derivative of true heavenly secrets or ordinances) while also being essentially worthless (inasmuch as they are flawed perversions of the real thing).

Other ancient texts, such as the Cave of Treasures, contain further variants of the fallen angels myth:

In these years there appeared those craftsmen of sin and disciples of Satan, for it was he who was their teacher. Into them went, took residence and spread the error-producing spirit by which took place the fall of Seth’s children. Jubal and Tubal-Cain, those two brothers, sons of Lamech the blind who had killed Cain, were the ones with whom appeared the art and craft of forging, hammer, pincers and anvil. … Tubal-Cain made cymbals, rattles, and tambourines. When lewdness and debauchery had waxed great among the children of Cain and when they had no other goal than only debauchery, they did not compel (anybody) to work nor did they have a chief or guide. … When the children of Seth heard this noisy uproar and laughter in the camp of Cain’s children, about 100 valiant men of them gathered and set their mind upon going down to the camp of the children of Cain. … When they saw that the daughters of Cain were beautiful to behold and exposed themselves without shame, the sons of Seth were inflamed by the fire of passion. (Likewise) when Cain’s daughters saw the beauty of the sons of Seth they rushed on them like wild animals and soiled their bodies. Thus Seth’s sons destroyed themselves by fornication with the daughters of Cain.30

In this account, the role of the Watchers (i.e., the fallen angels) is transferred primarily to Satan. He becomes the fallen angel who instructs Jubal and Tubal-Cain concerning their crafts, revealing the forbidden knowledge that would lead to sin and destruction. At the same time, the status of the Watchers as the “sons of God” is transferred to the sons of Seth. The story is no longer about heavenly angels who descend to earth in their lust after the daughters of men. Instead, it is about the sons of Seth who descend from a holy mountain in their lust after the daughters of Cain. Both of these variations in the story mirror the Book of Moses, which similarly treats Satan as the primary fallen angel and which depicts the “sons of God” as a righteous lineage of mortal beings.31

Revealing Secrets to the Wives

One final point of resemblance remains to be highlighted. This is the peculiar statement about Lamech revealing a secret to his wives in Moses 5:33–35:

For, from the days of Cain, there was a secret combination, and their works were in the dark, and they knew every man his brother. Wherefore the Lord cursed Lamech, and his house, and all them that had covenanted with Satan; for they kept not the commandments of God, and it displeased God, and he ministered not unto them, and their works were abominations, and began to spread among all the sons of men. And it was among the sons of men. And among the daughters of men these things were not spoken, because that Lamech had spoken the secret unto his wives, and they rebelled against him, and declared these things abroad, and had not compassion.

The essence of this detail, which is not found in the Genesis account, is corroborated by many ancient and medieval versions of the fallen angels myth. In 1 Enoch 7:1, for example, we read that the Watchers “took wives unto themselves, and … taught them magical medicine, incantations, the cutting of roots, and taught them (about plants).”32 In the Syncellus manuscript of 1 Enoch 8:3, it is reported that these angels “began to reveal mysteries to their wives.”33 In 1 Enoch 9:8 it is stated that the Watchers “lay together with them—with those women—and defiled themselves, and revealed to them every (kind of) sin.”34 It should be clarified that the wives are not the only recipients of these secrets, but they are often included or emphasized as obtaining particular types of knowledge from the Watchers.35

The theme is later picked up by Clement of Alexandria, who stated “that the angels who had obtained the superior rank, after having sunk into pleasures, told to the women the secrets that had come to their knowledge, whereas the rest of the angels concealed them.”36 Julius Africanus reportedly mentioned that when “humankind became numerous on the earth, angels of heaven had intercourse with daughters of men. … Then it was they who transmitted knowledge about magic and sorcery, as well as the numbers of the motion of astronomical phenomena, to their wives, from whom they produced the giants as their children.”37 Zosimus, an Egyptian alchemist writing in the 4th century AD, wrote that “ancient and divine scriptures said this, that certain angels lusted after women and, after descending, taught them … all the works of nature.”38 Another relevant ancient source comes from an Egyptian text called the Letter of Isis the Priestess to Horus:

… it came to pass that a certain one of the angels who dwell in the first firmament, having seen me (i.e., Isis) from above, was filled with the desire to unite with me in intercourse. He was quickly on the verge of attaining his end, but I did not yield, wishing to inquire of him as to the preparation of gold and silver. When I asked this of him, he said that he was not permitted to disclose it, on account of the exalted character of the mysteries, but that on the following day a superior angel, Amnael, would come … The next day, when the sun reached the middle of its course, the superior angel, Amnael, appeared and descended. Taken with the same passion for me he did not delay, but hastened to where I was. But I was no less anxious to inquire after these matters. When he delayed incessantly, I did not give myself over to him, but mastered his passion until he showed the sign on his head, and revealed the mysteries I sought, truthfully and without reservation.39

According to Reed, “in late antique Egypt, multiple variations of this narrative are integrated into ‘gnostic’ accounts of primeval history, as attested in Coptic in the Nag Hammadi codices. … it does not become integrated into known Jewish literature until the Middle Ages, when it emerges alongside Enochic traditions in the so-called ‘Midrash on Šemḥazai and Azael.”40 This midrashic text reads as follows:

Immediately they descended (to earth), and the evil impulse gained control of them. When they beheld the beauty of mortal women, they went astray after them, and were unable to suppress their lust, as Scripture attests: “and the sons of God saw, etc.” (Gen 6:2). Shemhazai beheld a maiden whose name was ’Asterah. He fixed his gaze upon her (and) said to her: “Obey me!” She answered him: “I will not obey you until you teach me the Inexpressible Name, the one which when you pronounce it you ascend to Heaven.” He immediately taught her, she pronounced it, and she ascended to Heaven.41

In this strain of the tradition, it may be notable that the women aren’t negatively portrayed as having caused the destruction of mankind, as is often implied or stated in other sources. Instead, their obtaining heavenly secrets is seen in a more positive light. This seems to align better, at least on a general level, with the Book of Moses, where Lamech’s wives are viewed as refusing to uphold the secrecy of his evil actions. Reed has drawn attention to the fact that some statements in 1 Enoch likewise have a more positive or neutral disposition towards the female recipients of the secret knowledge. In the Ethiopic version of 1 Enoch 19:3, for example, it is reported that the “women whom the angels have led astray will be peaceful ones.”42 This stands in contrast to the version of this passage in Codex Panopolitanus, which states that the wives of the angels would become sirens (seductive female beings in Greek mythology).43

It can therefore be seen that this motif gets repackaged in a variety of ways in different traditions. As observed by Reed, “It is perhaps telling that we find so much textual variation in the manuscript traditions surrounding the passages pertaining to women.”44 This diversity paves the way for the unique manifestation of this motif in Moses 5. Rather than heavenly angels revealing secrets to mortal women, it is instead Lamech, a mortal man, who conveys the forbidden knowledge to his wives. Nevertheless, within the Book of Moses the secret itself still has a supernatural origin grounded in the disclosure of a fallen angelic being, as it was first revealed to Cain by Satan (Moses 5:51). This mirrors the secrets conveyed to mankind in 1 Enoch by prominent fallen angels, such as Semyaz and Azaz’el. Moreover, there is also precedent for a mortal being like Lamech to be associated with the Watchers. This can be seen in the Cave of Treasures, where Cain’s posterity are viewed as fallen “sons of God” and thus take on the role of the fallen angels.

All of this is to say that the specific detail about Lamech revealing a forbidden secret to his wives in Moses 5:33–35 is conceptually aligned with these traditions. Although its manifestation of this motif is unique, that is not particularly surprising considering the already substantial variation within the extant sources themselves.

The Seduction Motif

Some ancient and medieval sources treat female seduction as being integral to the fall of the Watchers. In 1 Enoch it is reported that the angel Azaz’el not only taught the people how to make weapons of war but also “showed to their chosen ones bracelets, decorations, (shadowing of the eye) with antimony, ornamentation, the beautifying of the eyelids, all kinds of precious stones, and all coloring tinctures and alchemy. And there were many wicked ones and they committed adultery and erred, and all their conduct became corrupt” (1 Enoch 8:1–2).45

George Nickelsburg believes that, in at least one version of this myth, the “watchers were sent for the purpose of instructing humanity in righteousness, but they were seduced by the daughters of men,” who utilized the knowledge revealed to them by Azaz’el about enhancing beauty.46 As noted previously, the concept of female seduction also arises in the Codex Panopolitanus version of 1 Enoch 7:1, in which the wives of the fallen angels were said to become “sirens” (the Greek archetype for alluring females).47 Similar motifs and supporting evidence turn up in texts like Jubilees, Testament of Reuben, Targum Jonathan, Pseudo-Clementine Homilies, and Justin Martyr’s Second Apology.48

In the Cave of Treasures, the theme of female allurement surfaces with exceptional force. The text first establishes that the daughters of Seth were “chaste and undefiled” and that they and Seth’s posterity, generally, had no “impure desire or lewdness” (Cave 7:8–10). In contrast, it is later reported that “debauchery ruled among the children of Cain” and that “women shamelessly ran after men. … Abominable spirits entered into the women so that they were even more furious in their impurity than their daughters” (Cave 12:1–3). Eventually, when the sons of Seth “saw that the daughters of Cain were beautiful to behold and exposed themselves without shame, the sons of Seth were inflamed by the fire of passion. … Thus Seth’s sons destroyed themselves by fornication with the daughters of Cain” (Cave 12:16–17). While women are not portrayed as being exclusively at fault in this episode (seeing that men are also reproved for engaging in sexual deviance), the text seems especially attentive to the role of female allurement.

Within Joseph Smith’s account in Moses 5, the story of Cain and the introduction of secret combinations among his posterity doesn’t appear to contain any element of female seduction. However, there actually is a seduction narrative in Smith’s revelations that can be directly traced to secret works of darkness that were first taught to Cain by Satan. This comes from the Jaredite epic in the book of Ether, in which the daughter of Jared used her feminine wiles to reestablish her father’s control over the kingdom:

Now the daughter of Jared was exceedingly fair. And it came to pass that she did talk with her father, and said unto him: Whereby hath my father so much sorrow? Hath he not read the record which our fathers brought across the great deep? Behold, is there not an account concerning them of old, that they by their secret plans did obtain kingdoms and great glory? And now, therefore, let my father send for Akish, the son of Kimnor; and behold, I am fair, and I will dance before him, and I will please him, that he will desire me to wife; wherefore if he shall desire of thee that ye shall give unto him me to wife, then shall ye say: I will give her if ye will bring unto me the head of my father, the king. … And it came to pass that Akish gathered in unto the house of Jared all his kinsfolk, and said unto them: Will ye swear unto me that ye will be faithful unto me in the thing which I shall desire of you? … And it came to pass that thus they did agree with Akish. And Akish did administer unto them the oaths which were given by them of old who also sought power, which had been handed down even from Cain, who was a murderer from the beginning. (Ether 8:8–15)

Few readers have likely connected this episode to the fallen angels myth found in Enochic lore, but it provides a strikingly relevant scene.49 Forbidden secrets, unholy oaths, and the prominent role of female allurement—all of which are explicitly traced back to the covenant that Cain entered into with Satan. As Moroni explained just several verses later, these things were perpetuated “by the devil … who hath caused man to commit murder from the beginning” (Ether 8:25).

The Jaredite seduction narrative may be significant on another level as well. Moroni emphasized that these types of secret combinations eventually “caused the destruction of this people” (Ether 8:21), and the Nephites eventually termed the region where the Jaredites formerly dwelled as the land of “Desolation” (Alma 22:30). While Jared’s daughter didn’t single-handedly cause the destruction of the Jaredites, her ploy to get power provided an apt representation of the type of wickedness that did.

With this in mind, it is interesting that renditions of the seduction motif in the myth of the fallen angels sometimes describe a similarly destructive end. Concerning 1 Enoch 8:2, Nickelsburg explains that this verse “describes the result of the seduction of the holy ones—the earth is made desolate.”50 Likewise, just after remarking that the angels of heaven transmitted forbidden knowledge to their mortal wives, Julius Africanus states that “when depravity came into being because of them, God resolved to destroy every class of living things in a flood.”51 In the Cave of Treasures, we read that “Seth’s sons destroyed themselves by fornication with the daughters of Cain.”52 Over and over again, promiscuity is tied to spiritual downfall or physical destruction in the fallen angels myth.

In summary, if the Nephites inherited a similar tradition, in which a seduction narrative or motif was in some way integrated into the account of the moral decline of the “sons of God” in antediluvian times, then it would very much help explain why Moroni chose the story of Jared’s daughter in Ether 8 as a springboard into his extended denunciation of secret combinations. He may have viewed this episode of Jaredite history as being particularly emblematic of the destructive outcomes of Satan’s secret works of darkness.

Conclusion

It must be emphasized, once again, that the Genesis account doesn’t feature most of the parallels described throughout this article. It never says anything about Cain’s association with Satan. It never hints that Satan or other fallen angels were revealing forbidden knowledge to mankind. It doesn’t remark on secrets being revealed to wives. Nor does it contain a seduction narrative associated with this period of antediluvian history. Thus, on multiple levels, the Book of Moses (and, in one instance, the Book of Mormon) align with particular themes and motifs found in extrabiblical sources but which aren’t contained in the Bible itself.

This isn’t to say that Smith’s revelations perfectly reflect these traditions. Indeed, none of the expressions of these motifs in restored scripture are precisely the same as they occur in extrabiblical texts. At the same time, however, it must be acknowledged that there is substantial variation in the extant sources themselves. When viewed in light of this fact, the Book of Moses and Book of Mormon present what may appropriately be viewed as variations on a theme. They interact in different ways with multiple traditions surrounding the fallen angels myth, yet their contents do not appear to be directly derivative of any of them. They thus plausibly come across as ancient—and, yet, original—sources belonging to this same complex of traditions.

This is especially so when one considers the nuances of many parallels throughout Smith’s revelations. It seems difficult to imagine, for instance, that Joseph Smith would have been familiar with Cain’s legacy in ancient traditions as well as the Hebrew meaning of his name, and that he would then be able to so thoroughly integrate these features into the Book of Mormon, only to later provide the textual backdrop in the Book of Moses.53

Likewise, it is fascinating that the secrets revealed to mankind by angelic beings in the extrabiblical sources so frequently have ties with priesthood ordinances and doctrines found in connection to Latter-day Saint temple worship. The role of Satan, the angelic messengers, the secret or sacred nature of the teachings, the emphasis on oaths, the signs given to demonstrate covenantal loyalty, the penalties for disclosing them, and other factors all point to a ritual complex that becomes especially apparent to those familiar with Latter-day Saint temple worship and ordinances. This all makes sense once one recognizes that the secret combinations in the Book of Moses are subtly portrayed as an evil counterfeit to God’s true priesthood covenants and ordinances.

Some may assume Joseph Smith simply extracted all this information from 1 Enoch, which was potentially available to him in 1829–1830. While that could account for some of the data highlighted throughout this article, it falls short of accounting for it all. Moreover, Smith’s access to that text, especially in its entirety, is unproven and doubtful for several reasons.54 Overall, his revelations come across as plausibly authentic when it comes to this particular set of details, thus supporting his status as a genuine prophet of God who was called to restore ancient truths.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Enoch and the Gathering of Zion: The Witness of Ancient Texts for Modern Scripture (Interpreter Foundation, with Scripture Central and Eborn Books, 2021), 45.

Matthew L. Bowen, “Getting Cain and Gain,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 15 (2015): 115–141.

Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and David J. Larsen, In God’s Image and Likeness 2: Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel (The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014).

Relevant Scriptures

Book of Mormon

Ether 8:8–15

Ether 8:25

Book of Moses

Moses 5:24

Moses 5:25

Moses 5:29–31

Moses 5:33–35

Moses 5:49–53

Moses 5:58–59

Moses 7:33

- 1. See Matthew L. Bowen, “Getting Cain and Gain,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 15 (2015): 115–141; Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Wordplay on Cain,” Evidence 267 (November 8, 2021). For a somewhat related theme, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Wordplay on Jared,” Evidence 511 (September 10, 2025).

- 2. Bowen, “Getting Cain and Gain,” 116.

- 3. The case for this wordplay proposal is considerably strengthened by an analogous treatment of Cain’s name and legacy in the writings of an ancient Jewish historian named Josephus. He described Cain as “wholly intent upon getting” and as producing a sacrifice that was “gotten by forcing the ground.” Moreover, Cain “only aimed to procure every thing that was for his own bodily pleasure, though it obliged him to be injurious to his neighbours. He augmented his household substance with much wealth, by rapine and violence: he excited his acquaintance to procure pleasure and spoils by robbery: and became a great leader of men into wicked courses. He also introduced a change in that way of simplicity wherein men lived before; and was the author of measures and weights.” Josephus also writes that “even while Adam was alive it came to pass, that the posterity of Cain became exceeding wicked; every one successively dying one after another more wicked than the former: they were intolerable in war, and vehement in robberies; and if any one were slow to murder people, yet was he bold in his profligate behaviour; in acting unjustly, and doing injuries for gain.” William Whiston, trans., The Works of Flavius Josephus (London, 1737), Book 1, chapter 2.

- 4. For a related article on this topic, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Traditions of Cain,” Evidence 306 (February 7, 2022).

- 5. Life of Adam and Eve (Apocalypse) 2:4. Translation by M. D. Johnson, “Life of Adam and Eve,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 2 vols., ed. James Charlesworth (Doubleday, 1983–1985), 2:267.

- 6. Life of Adam and Eve (Apocalypse) 7:2. Translation by Johnson, “Life of Adam and Eve,” 273.

- 7. Apocalypse of Abraham 24:5. Translation by R. Rubinkiewicz, “Apocalypse of Abraham,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1:701.

- 8. Joseph Benzion Witztum, The Syriac Milieu of the Quran: The Recasting of Biblical Narratives (Dissertation, Princeton University, 2011), 135. In addition to the sources cited below, see also Johannes Glenthøj, Cain and Abel in Syriac and Greek Writers (4th–6th Centuries) (Louvain: Peeters, 1997), 280–281.

- 9. Theophilus of Antioch (d. 183–85), Ad Autolycum 2.29 (ET in the edition of Robert M. Grant, [Oxford, 1970], 73); as cited in Joseph Benzion Witztum, The Syriac Milieu of the Quran: The Recasting of Biblical Narratives (Dissertation, Princeton University, 2011), 135.

- 10. S. Brock, “Two Syriac Dialogue Poems on Abel and Cain”, Le Muséon 113 (2000): 333–375; as cited in Witztum, The Syriac Milieu of the Quran, 135.

- 11. Ms. Vat. Syr. 120, ff. 172b–185b; as translated and cited in Witztum, The Syriac Milieu of the Quran, 136.

- 12. See Scripture Central, “Book of Moses Evidence: Satan, Father of the Wicked,” Evidence 495 (May 21, 2025). For an exploration of the covenantal use of the terms “love” and “hate” in the Book of Mormon, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Love and Hate,” Evidence 402 (April 25, 2023).

- 13. Brigham Young taught, “Your endowment is, to receive all those ordinances in the house of the Lord, which are necessary for you, after you have departed this life, to enable you to walk back to the presence of the Father, passing the angels who stand as sentinels, being enabled to give them the key words, the signs and tokens, pertaining to the holy priesthood, and gain your eternal exaltation.” Discourses of Brigham Young, sel. John A. Widtsoe (1954), 416; as cited in “Endowment,” Topics and Questions, online at churchofjesuschrist.org. See also Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Freemasonry and the Origins of Latter-day Saint Temple Ordinances (Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2022), 137–151.

- 14. S. C. Malan, trans., The Book of Adam and Eve also called The Conflict of Adam and Eve with Satan (London: Williams and Norgate, 1882), 95.

- 15. Malan, The Book of Adam and Eve, 97.

- 16. Translation by Alexander Toepel, “The Cave of Treasures: A New Translation and Introduction,” in Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: More Noncanonical Scriptures, vol. 1, ed. Richard Bauckham, James R. Davila, and Alexander Panayotov (Eerdmans, 2013), 544. See also the Testament of Adam 3:5.

- 17. In the Book of Moses, Cain desired to obtain Abel’s flocks (Moses 5:33). In the Conflict of Adm and Eve and the Cave of Treasures, Cain desired to obtain the wife that Adam and Eve had set aside for Abel.

- 18. Ernest A. Wallis Budge, trans., The Book of the Bee: The Syriac Text (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1886), 26.

- 19. W. Lowndes Lipscomb, The Armenian Apocryphal Adam Literature (Peeters Publishers, 1990), 273.

- 20. Gary A. Anderson and Michael E. Stone, eds., A Synopsis of the Books of Adam and Eve, Second Revised Edition (Scholars Press, 1999), 30E–31E.

- 21. See Loren T. Stuckenbruck, The Myth of Rebellious Angels: Studies in Second Temple Judaism and New Testament Texts (Eerdmans, 2017); Angela Kim Harkins, Kelley Coblentz Bautch, and John C. Endres, eds., The Watchers in Jewish and Christian Traditions (Fortress Press, 2014).

- 22. Annette Yoshiko Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets? Women, Angels, and the Problem of Misogyny and ‘Magic’,” in Daughters of Hecate: Women and Magic in the Ancient World, ed. Kimberly B. Stratton and Dayna S. Kalleres (Oxford University Press, 2014), 111.

- 23. See George W. E. Nickelsburg and James C. VanderKam, 1 Enoch 1: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch Chapters 1–36, ed. Klaus Baltzer (Fortress Press, 2012), 304. For the discussion of the term Beqa and its potential meaning within the Jewish gematria, see p. 306. For the bracketed concept of “remember,” see p. 304n.b. For the translation of this idea as “memorize,” see E. Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1:48.

- 24. George W. E. Nickelsburg and James C. VanderKam, 1 Enoch 2: A Commentary on the Book of 1 Enoch Chapters 37–82, ed. Klaus Baltzer (Fortress Press, 2012), 305.

- 25. Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch 2, 307.

- 26. Translation by Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 48–49.

- 27. See Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Freemasonry and the Origins of the Latter-day Saint Temple Ordinances (Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2022), 137–150. For further commentary on this portion of 1 Enoch, see Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and David J. Larsen, In God’s Image and Likeness 2: Enoch, Noah, and the Tower of Babel (The Interpreter Foundation and Eborn Books, 2014), 250–251; Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, Enoch and the Gathering of Zion: The Witness of Ancient Texts for Modern Scripture (Interpreter Foundation, with Scripture Central and Eborn Books, 2021), 45.

- 28. For an onomastic study which sheds light on this matter, see Matthew L. Bowen, “‘Swearing by Their Everlasting Maker’: Some Notes on Paanchi and Giddianhi,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 28 (2018) : 155–170.

- 29. Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 126.

- 30. Toepel, “The Cave of Treasures,” 549.

- 31. This is a prominent theme in the Book of Moses. See Moses 1:12–13; 6:68; 7:1; 8:13. For more on this topic, see Scripture Central, “Book of Moses Evidence: Wordplay on Moses,” Evidence 477 (January 15, 2025). Stephen O. Smoot, “‘I Am a Son of God’: Moses’ Prophetic Call and Ascent into the Divine Council,” in Tracing Ancient Threads in the Book of Moses: Inspired Origins, Temple Contexts, and Literary Qualities, Volume 2, ed. Jeffrey M. Bradshaw, David Rolph Seely, John W. Welch, and Scott A. Gordon (The Interpreter Foundation; Eborn Books, 2021), 923–942.

- 32. Translation by Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 16.

- 33. Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 115.

- 34. Translation by Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 17.

- 35. For instance, concerning root-cutting and plant lore (associated with potions and often magic in ancient sources) Reed acknowledges that “in the Greek translations of the Book of the Watchers, the association of these skills with women’s magic does appear to have been enhanced.” Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 119.

- 36. Clement, Strom. 5.1.10.2; as cited in Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 127.

- 37. Sync. 19.24–20.4; as cited in Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 147.

- 38. Sync. 14.6–14; as cited in Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 127.

- 39. M. Berthelot and C. É. Ruelle, Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs, 2 vols. (Paris:

- 40. Annette Yoshiko Reed, “Fallen Angels and the Afterlives of Enochic Traditions in Early Islam,” 1st Nangeroni Meeting of the Early Islamic Studies Seminar (June 15–19, 2015), 18.

- 41. Translation provided by John Reeves as part of the course material for one of his classes. For further interaction with this work, see John C. Reeves, Jewish Lore in Manichaean Cosmogony: Studies in the Book of Giants Traditions (Hebrew Union College Press, 1992), 84–88. It should also be pointed out that this account resonates with the secret name revealed to the angel Michael, which name was then inappropriately conveyed to mankind, as reported in 1 Enoch 69:14–15 (discussed previously).

- 42. Translation by Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 23.

- 43. See Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 23n.c. See also Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 125.

- 44. Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 122.

- 45. Isaac, “1 (Ethiopic Apocalypse of) Enoch,” 16.

- 46. Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch 1, 196.

- 47. See Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 120–121, 125.

- 48. See Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch 1, 194–196. There is some debate, however, as to whether or not the theme of female seduction in 1 Enoch is an original feature of the text. While Nickelsburg believes it is, scholars such as Siam Bhayro and Annette Reed suspect the seduction motif was most likely a later textual development. See Reed “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 121–122. What can be said with confidence is that the Book of Moses interacts with a genuinely ancient Enochic element that proliferated into various textual traditions over time. Determining its source is beyond what the available evidence can either prove or disprove.

- 49. For discussions of this topic, see Alan Goff, “The Dance of Reader and Text: Salomé, the Daughter of Jared, and the Regal Dance of Death,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 57 (2023): 1–52;

- 50. Nickelsburg and VanderKam, 1 Enoch 1, 196.

- 51. Sync. 19.24–20.4; as cited in Reed, “Gendering Heavenly Secrets?” 147.

- 52. Toepel, “The Cave of Treasures,” 549.

- 53. For the treatments of Cain in the Book of Mormon, see Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Wordplay on Cain,” Evidence 267 (November 8, 2021); Scripture Central, “Book of Mormon Evidence: Traditions of Cain,” Evidence 306 (February 7, 2022). For a discussion of how many Book of Mormon passages, including the traditions about Cain, trace back to the Book of Moses, see Noel B. Reynolds, “The Brass Plates Version of Genesis,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 34 (2020): 63–96; Jeff Lindsay and Noel B. Reynolds, “‘Strong Like unto Moses’: The Case for Ancient Roots in the Book of Moses Based on Book of Mormon Usage of Related Content Apparently from the Brass Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 44 (2021): 1–92, esp. 56; Jeff Lindsay, “Further Evidence from the Book of Mormon for a Book of Moses-Like Text on the Brass Plates,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 61 (2024): 415–494; Jeff Lindsay, “Parallels between the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon, Part 1: Details of Their Distribution and Relationships to the JST,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 67 (2025): 275–320; Jeff Lindsay, “Parallels between the Book of Moses and the Book of Mormon, Part 2: The Updated List of 146 Parallels,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 67 (2025): 321–370.

- 54. See Jeffrey M. Bradshaw and Ryan Dahle, “Could Joseph Smith Have Drawn on Ancient Manuscripts When He Translated the Story of Enoch?: Recent Updates on a Persistent Question,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 33 (2019): 305–374, esp. 308–311; For reasons to be cautious in assuming it was implausible for Joseph Smith to have learned anything about 1 Enoch, see Colby Townsend, “Revisiting Joseph Smith and the Availability of the Book of Enoch,” Dialogue 53, no. 3 (2020): 41–71.